A while back, when I was looking through my archives of old documents, files, and game CDs, one particular item caught my attention. It was an original CD for the Polish version of Colin McRae Rally 3 by Codemasters. When I played this game as a kid, I was terrible at it. Now the time has come to get revenge.

Colin McRae Rally 3 is a rally game, i.e. you race cars on special point-to-point stages in a time attack format. The fastest driver over the entire rally wins it, and the driver with the most points from rallies in a season wins the championship. Now the progression system of Colin McRae Rally 3 was tied to winning championships — as in you would unlock cars, upgrades, etc. with every championship win. You could see how this could become a problem for an unskilled player such as past me.

That said, the game also had a cheat system. When you went to the game settings, there was a special “secrets” menu, that allowed you to input codes to unlock things that you would normally unlock via game progression. To get the codes, you would have to either call a phone number, or to go to a special website, and provide a 4-digit “secret access code” to get your secret codes back. As is often the case in life, this was a paid service.

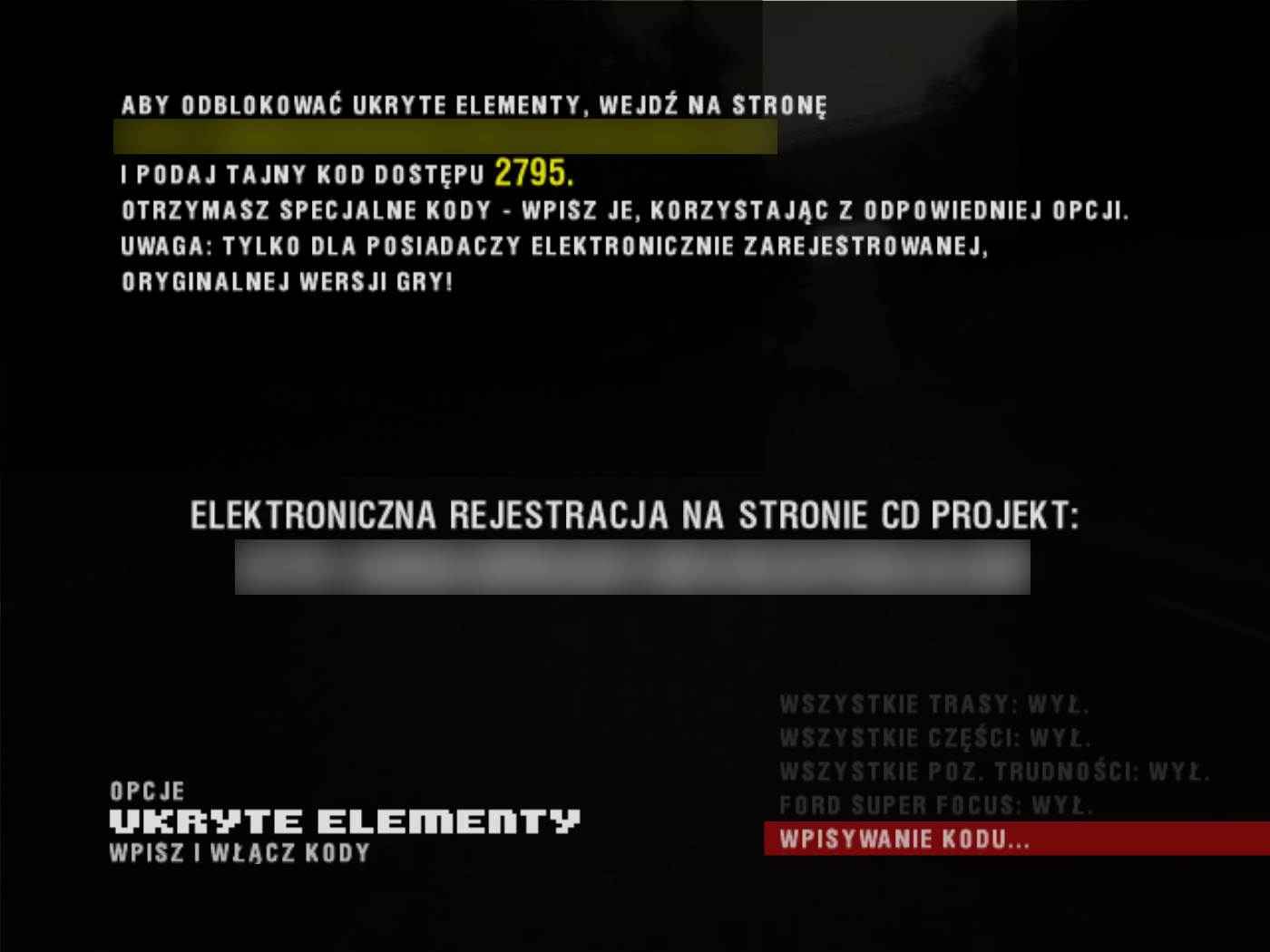

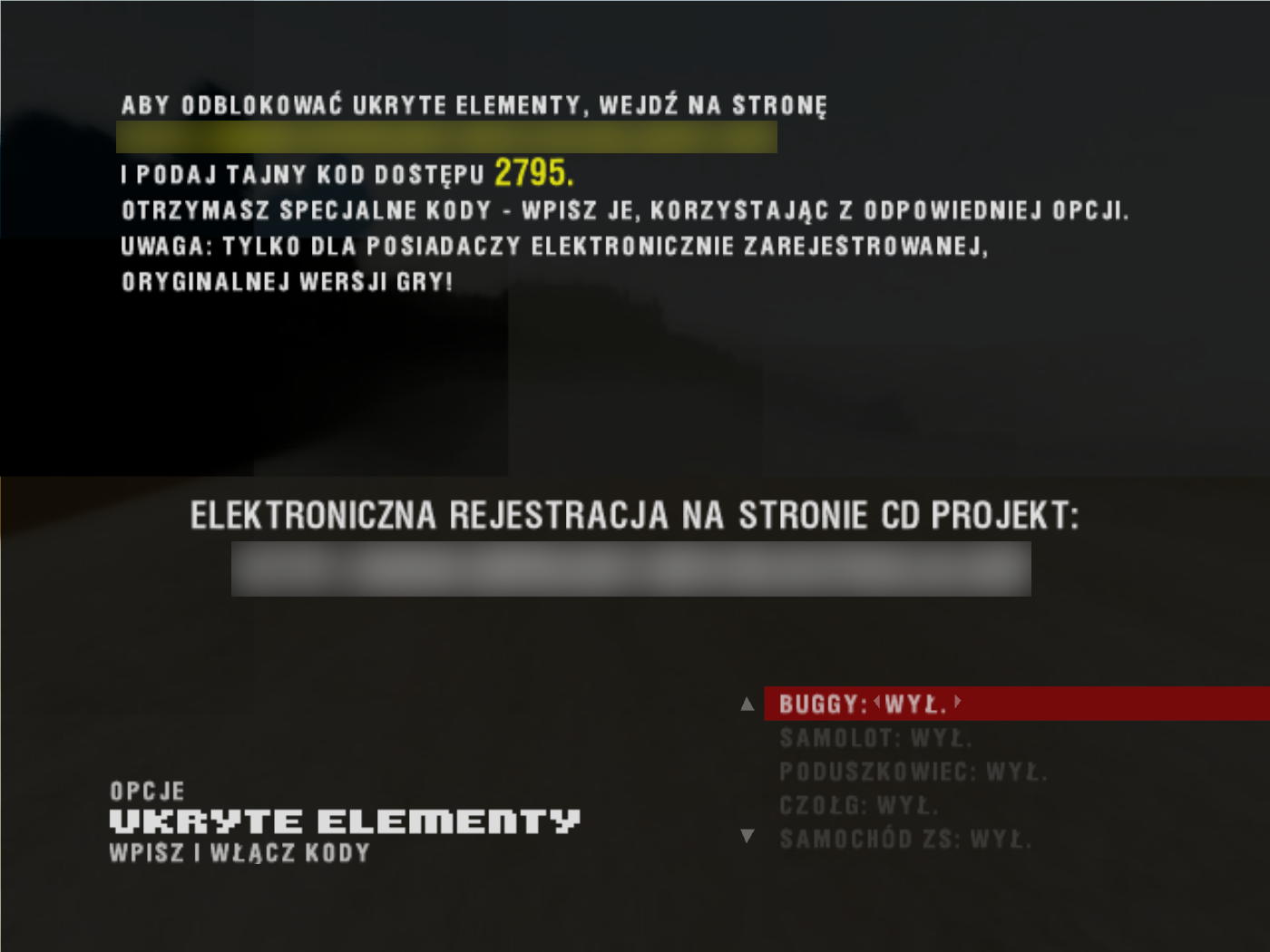

For non-Polish speakers, the above says:

To unlock hidden content, go to [REDACTED] and provide the secret access code 2795. You will receive special codes — enter them using the appropriate option. Warning: only for owners of electronically registered, original copies of the game!

I’ve redacted the URLs, which used to lead to CD Projekt’s old site. I’ve done it because the links are dead, the pages are not on the Internet Archive, and someone else owns the domain now and the content hosted therein looks quite suspicious.

Codemasters themselves also used to have their own similar page to access these, but it is also gone — it has been almost 20 years by now, after all. Only thanks to the good graces of the Internet Archive may we check out how the website where you could get the codes actually looked like.

Mmm, that 2000s web design.

Now back then, I was a kid, and therefore was not in free possession of money, especially not $5.49 money (don’t laugh, it was 2000s Poland), so I never ended up calling the number or going to the website. And even if I had, the codes would be probably pretty useless for me now, because the “secret access code” changes with every installation. Figures.

Searching online, I found some special codes around, but each site that had them had them tied to a specific “secret access code”, which didn’t help me much. The advice offered by those sites is that if you get a different “secret access code” than what they had, then you should delete the game’s save files and launch it again, in the hope that the “secret access code” generator somewhere inside the game would luck out and pick one of those specific known ones on next launch. This is a method one could use, but it is barbaric and I will not stand for it. Not good enough.

After excluding that possibility, I figured that Codemasters is still a company that is active to this day, and they have a support contact form up. So I tried that, and got a reply back that the cheat codes are no longer available, but all of the features locked behind them can be unlocked by playing the game normally.

Now I’m not sure about the claim that everything is unlockable via game progression. Some online sources claim that some of the wackier vehicles (the jet, the hovercraft, the buggy, and the tank) are not unlockable using any other method than cheats. I’m not sure whether that is actually the case, though.

That said, the codes no longer being available meant one thing to me. It was time to get WinDbg out the closet. And learn some Ghidra, too.

I’ve been looking for an excuse to do some reversing for long enough.

Finding the locks

Now, as excited as I was to try and break this thing, it only took me approximately 17 seconds to realise that what I have is: a megabytes-large executable in front of me to somehow find the special codes in, a bunch of tools that I have used either very sparingly or never at all, and no idea where to even begin. The first few hours were spent on just kind of prodding different associated game files, grepping strings, and seeing if anything looked close to what I was looking for. That did not yield any results.

Slightly discouraged, I started reading up on random Google search results in search of inspiration. The breakthrough — incredibly obvious, in retrospect — came in when I was reading up on Cheat Engine on Wikipedia, and the first sentence mentioned that the program in question was a “memory scanner”. I began to wonder if I had any use for a memory scanner — and I realised that yes, a memory scanner would come in helpful here.

The chain of thinking goes somewhere like this:

- There is a black-box process here I want to reverse. There is an input I control, and a pass/fail result.

- I control the input freely. This means, that if I can take a snapshot of the game process’s memory that I can search, and I use a sufficiently distinctive string and send it to the game for checking, I will see any and all instances of this string in the process’s memory.

- If I can see all of the instances of the string, I will be able to see the memory addresses under which they reside.

- Which means that I may be able to add data breakpoints, and intercept both writes and reads of those addresses. One of the reads must come from the part of the game executable that is actually checking the special codes, and will serve as my entry point for investigation.

The execution of the above plan began by me capturing a “time travel” trace of the process using WinDbg. A “time travel” trace has the full history of execution of the process, that I can step forwards and backwards through at my leisure. I put in ABABACADA in the password input, attached WinDbg to the game process to capture the trace, and pressed the “enter” button on the code entry screen in hopes of capturing the moment I wanted.

Then, using the captured trace, I used the Search Memory command to find my controlled string.

0:036> s -a 0 L?80000000 "ABABACADA"

006419b8 41 42 41 42 41 43 41 44-41 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ABABACADA.......

006f7e68 41 42 41 42 41 43 41 44-41 00 55 20 44 4f 20 55 ABABACADA.U DO U

That is two addresses to search through. First, I tried to add naive data breakpoints at both of these addresses, using Break on Access:

0:036> ba r1 0x006419b8

0:036> ba r1 0x006f7e68

but quickly realised that those breakpoints were seeing too many hits and trying to decipher which one did which was way too inefficient. As my philosophy here was to get to my goal as quickly as possible, what I was looking for is some kind of discriminator to be able to tell with a large degree of probability where to begin.

A feature of the “preview” flavour of WinDbg, closely tied to the “time travel” tracing, is a “timeline” feature that allows you to add specific breakpoints, and spits back a timeline graph of where those breakpoints are getting triggered. I decided to try it out and told it to plot all accesses to both of the addresses above, and got this image back:

This image was curious, because there is a lot of spaced-apart accesses, but there is one, marked with the blue arrow above, that looks suspiciously out of alignment with the others. The thinking goes, that the other accesses are simply part of the game’s rendering loop (i.e. the game re-reads the code stored in memory to draw it back to the screen), and this one lone access is the one I’m actually looking for. The access was paired with an instruction pointer value, which meant that now it was time to examine the code behind this irregular access.

Picking a lock

Being reasonably sure that this was the entry point I was looking for all along, I fired up Ghidra and navigated to the instruction pointer address in question. After some deciphering work of the function found therein, including renaming variables for understanding, I ended up with something along the lines of:

undefined4 FUN_00411fa0(byte *userCode,int *param_2)

{

undefined4 accessCode;

byte *userCodeIterator;

byte *referenceCodeIterator;

int i;

bool bVar1;

byte local_8 [8];

int indexOfCodeToCheck;

byte userCharacter;

i = 0;

do {

indexOfCodeToCheck = i;

accessCode = FUN_0042ba40(i);

FUN_00412150(local_8,7,accessCode,indexOfCodeToCheck);

referenceCodeIterator = local_8;

userCodeIterator = userCode;

do {

userCharacter = *userCodeIterator;

bVar1 = userCharacter < *referenceCodeIterator;

if (userCharacter != *referenceCodeIterator) {

fail:

indexOfCodeToCheck = (1 - (uint)bVar1) - (uint)(bVar1 != 0);

goto result;

}

if (userCharacter == 0) break;

userCharacter = userCodeIterator[1];

bVar1 = userCharacter < referenceCodeIterator[1];

if (userCharacter != referenceCodeIterator[1]) goto fail;

userCodeIterator = userCodeIterator + 2;

referenceCodeIterator = referenceCodeIterator + 2;

} while (userCharacter != 0);

indexOfCodeToCheck = 0;

result:

if (indexOfCodeToCheck == 0) {

*param_2 = i;

return 1;

}

i = i + 1;

if (9 < i) {

return 0;

}

} while( true );

}

Now this definitely looks like what I’m interested in here. I managed to decipher that one of the pointers here (userCodeIterator) was pointing to the buffer I had control over, the other was not controlled by me, but rather generated by one of the mysterious functions, and the code was comparing those against each other, 2 bytes at a time. This is what a “check this special code” function could look like.

What this means, in turn, is that I can take the two comparisons of userCodeIterator and referenceCodeIterator, go to the disassembly, get the instruction pointer values for those comparison instructions, and then set breakpoints there. With the breakpoints, I can exfiltrate a special code byte-by-byte with the following scheme:

- Choose an entirely random password x.

- Set breakpoints at both comparisons.

- Type x into the special code input.

- Let the game check the code, but examine results of all comparisons via the breakpoint.

- If the comparison of the i-th byte passes, then there is nothing to do.

- If the comparison of the i-th byte fails, then examine the byte that that comparison was against, change the i-th character of x for it, and input x again.

- As the password is necessarily finite, this process will terminate with x being the correct password.

I tried the above procedure, which gave me a code of XARIWQ, and unlocked the first item on the list, the buggy car!

Figuring out the mechanism

Well, getting one code is cool and all, but getting all of them is proportionally cooler, right? As luck would have it, discovering the key to that was not far. Astute readers may have noticed that in the decompiled snippet above, the referenceCodeIterator was assigned to local_8, which was previously passed to a mysterious FUN_00412150. Well, that is a function we can inspect. Let’s see, then.

undefined4 FUN_00412150(char *bonusCode,uint magic,uint accessCode,uint specialCodeIndex)

{

undefined4 uVar1;

uint uVar2;

uint uVar3;

uint uVar4;

uVar1 = 0;

if (((accessCode < 10000) && (specialCodeIndex < 100)) && (6 < magic)) {

uVar3 = accessCode % 100 ^ specialCodeIndex % 100;

uVar2 = (uint)(((ulonglong)accessCode / 100) % 100) ^ specialCodeIndex % 100;

uVar4 = 0x39;

if (uVar3 == 0) {

uVar4 = 1;

}

else {

while (uVar3 = uVar3 - 1, uVar3 != 0) {

uVar4 = (uVar4 * 0x39) % 0x44a5;

}

}

uVar3 = 0x39;

if (uVar2 == 0) {

uVar3 = 1;

}

else {

while (uVar2 = uVar2 - 1, uVar2 != 0) {

uVar3 = (uVar3 * 0x39) % 0x44a5;

}

}

bonusCode[6] = '\0';

*bonusCode = 'Z' - (char)((ulonglong)uVar4 % 0x1a);

bonusCode[1] = 'Z' - (char)(((ulonglong)uVar4 / 0x2a4) % 0x1a);

bonusCode[2] = 'Z' - (char)(((ulonglong)uVar4 / 0x1a) % 0x1a);

bonusCode[3] = 'Z' - (char)(((ulonglong)uVar3 / 0x1a) % 0x1a);

bonusCode[4] = 'Z' - (char)(((ulonglong)uVar3 / 0x2a4) % 0x1a);

bonusCode[5] = 'Z' - (char)((ulonglong)uVar3 % 0x1a);

uVar1 = 1;

}

return uVar1;

}

Given the code above, the trivial thing is to just paste it into a C compiler, or rewrite it in some other language, and check if the output is correct. Which I did, and it was. The codes were right. But that’s cheap. Let’s analyse this a bit and see if we can deduce what makes this box really tick.

As far as the parameters go, we have:

bonusCodeis the buffer in which the special code will be placed.magicis… I don’t know whatmagicis. It’s hardcoded to 7 at the call site, and always tested against 6. Some kind of anti-tamper mechanism, perhaps? Can’t say I care too much.- In debugging,

accessCodewas0xAEB, which is… 2795. Bingo! That’s our “secret access code”. specialCodeIndexwould end up being called with different, but sequential values: zero, one, etc. I eventually deduced that it was the index of the item on the list of unlockables to generate a special code for.

That definitely looks promising. Now, onto the locals.

uVar3is essentially 2 last digits of the “secret access code” XOR’d with the special code index. (That second part is modulo 100, but we can disregard this as going over 100 is impossible due to the preceding guard condition.)uVar2is 2 first digits of the “secret access code” XOR’d with the special code index.

Then, we have some mysterious constants, and then we have some modular arithmetic. This lit up a long-unused part of my brain and made me remember a mathematical construction that looked vaguely familiar to this when I squinted at it, and ended up being a direct hit.

Brief detour: Finite fields

Now, I have never been any good at abstract algebra, so I will not attempt to explain the technicalities of the algebraic constructions that I will speak of, lest I fail miserably. This is going to be the “cliff notes” version. (Any persons reading this with adequate mathematical skills: please don’t yell at me too much.)

A finite field, also known as a Galois field, is, well, a field. Namely, it is a finite set of elements, combined with two arbitrary binary operations, that we will arbitrarily call “addition” and “multiplication”, Those names are immediately suggestive, but the point here is that those operations could really be anything, so long as they adhere to some particular basic laws, those laws being:

-

Both of the operations are associative. When one type of operation is chained, you can arbitrarily reorder the application of the operation and get the same result, as long as the operands are not reordered.

In math speak this is written as:

- \((a + b) + c = a + (b + c)\) (for addition)

- \((ab)c = a(bc)\) (for multiplication)

-

Both of the operations are commutative. When the operands of each binary operation are swapped, the result remains the same:

- \(a + b = b + a\) (for addition)

- \(ab = ba\) (for multiplication)

-

Both operations are distributive with respect to each other. This is not easily explained in terms of words, but should be more intuitive when written down as formulae:

- \(a(b + c) = ab + ac\) (left-distributivity of multiplication over addition)

- \((a + b)c = ac + bc\) (right-distributivity of multiplication over addition)

-

Both operations have an identity element in the field that, when combined with any other element, does not change the result:

- \(a + 0 = a\) (identity element of addition)

- \(a \cdot 1 = a\) (identity element of multiplication)

At this point note that in this general definition, the 0 and 1 above are intended to be abstract terms, rather than the actual numbers 0 and 1. Those particular values make sense in normal maths and for the normal definition of these operators, but here we are describing a theoretical construction wherein both of these can be anything as long as it’s an element of the field. (Did I mention that abstract algebra is confusing?)

-

Both operations are invertible, i.e.

- For each element \(a\) of the field, there exists an element, denotated as \(-a\), such that \(a + (-a) = 0\).

- For each element \(a\) of the field, there exists an element, denotated as \(a^{-1}\), such that \(a a^{-1} = 1\).

Again, here the \(-a\) and \(a^{-1}\) things are “normal math notations”, but that does not mean that the elements described here are negative or fractional. All depends on what addition and multiplication mean in this particular field.

Okay, so all that is what a standard field is. Now, for our purposes, a finite field has one extra interesting property, namely that in each finite field, there is at least one element \(a\), which we’ll name the primitive element, such that all of the other non-zero elements of the field can be computed by

\[a, a^2, a^3, \dots, a^{q - 2}, a^{q - 1} = 1\]wherein \(q\) is the order of the group, or in other words, the number of its elements.

Put in speaking terms, if you take the primitive element of the group, and then iteratively apply the multiplication operation on it \(q - 1\) times, you will get all of the non-zero elements back. Which is pretty neat.

Now, as it turns out, finite fields can be spawned out of prime numbers and modular arithmetic. If you take a prime number \(p\), then using modular arithmetic, you can fabricate a finite field by taking the integers modulo \(p\), which real mathheads denote as \(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}\). The addition and multiplication operations in a modulo \(p\) field are a little funky and are defined as:

- (addition): \(a + b := (a + b) \mod p\)

- (multiplication) : \(ab := ab \mod p\)

The notation above is definitely confusing. The way to read is that more or less, in the world of integers modulo \(p\), you can compute everything like in “normal” math, but then you take it modulo \(p\) after each operation.

For the brevity of this, let’s just accept the fact that a field defined in such a manner meets all of the field axioms described above, and is a finite field. Proving this is a bit beside the point of this post, and probably has been done to death by enough people already.

Now, after this intermission, we can go back to our secret constants…

So, our constants were: 0x39, and 0x44a5. Let’s examine those in some more detail.

0x44a5 is, in decimal, 17573, and in fact it is the 2020th prime number. So \(\mathbb{Z}/17573\mathbb{Z}\) is a finite field. Given that 0x39, or 57 in decimal, is being iteratively exponentiated modulo 17573 in the code generation process, then may it be a primitive element of this field? Finding out the answer to this is easy enough to brute force if you have a computer. Here’s a crude C# program that does it.

namespace GaloisFieldChecker

{

public static class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

if (args.Length != 2

|| !uint.TryParse(args[0], out uint q)

|| !uint.TryParse(args[1], out uint a)

|| a <= 1

|| a >= q)

{

printUsage();

return;

}

var generatedElements = new HashSet<uint>();

uint element = a;

for (int i = 0; i < q; ++i)

{

generatedElements.Add(element);

element *= a;

element %= q;

}

Console.WriteLine(generatedElements.Count == q - 1

? $"{a} is a primitive element of GF({q}), as all numbers 1..{q - 1} have been generated by iterative exponentiation."

: $"{a} is not a primitive element of GF({q}). Only {generatedElements.Count} numbers have been generated by iterative exponentiation.");

}

private static void printUsage()

{

Console.Error.WriteLine(@"USAGE: GaloisFieldChecker.exe q a

where:

- q is the order of the Galois field (the field being the integers mod q)

- a is the element to check for being a primitive element of GF(q), 1 < a < q

Warning: The primality of q is not checked. Doing so is left as an exercise for the user.");

}

}

}

As it turns out, the above program claims that 57 indeed is the primitive element of the finite field of integers modulo 17573. Translating this into direct, practical terms, it means that the programmer of this special code generator managed to encode generating a permutation of 17572 distinct values, using just 2 integers, and some iterative computation. That’s pretty cool, but we’re looking for a code made of text characters, so what does that number have to do with anything?

Well, the two loops in the decompiled function compute \(57^{\texttt{uVar3}} \mod 17573\) and \(57^{\texttt{uVar2}} \mod 17573\), so two integers in the range [1, 17573]. Then, there is this snippet:

bonusCode[6] = '\0';

*bonusCode = 'Z' - (char)((ulonglong)uVar4 % 0x1a);

bonusCode[1] = 'Z' - (char)(((ulonglong)uVar4 / 0x2a4) % 0x1a);

bonusCode[2] = 'Z' - (char)(((ulonglong)uVar4 / 0x1a) % 0x1a);

bonusCode[3] = 'Z' - (char)(((ulonglong)uVar3 / 0x1a) % 0x1a);

bonusCode[4] = 'Z' - (char)(((ulonglong)uVar3 / 0x2a4) % 0x1a);

bonusCode[5] = 'Z' - (char)((ulonglong)uVar3 % 0x1a);

Three realisations here make this all come together in a neat bow:

- First of all,

0x1ais 26, and0x2a4is 676, or \(26^2\). - In the baseline Latin alphabet, there are 26 characters.

- \(26^3\) is 17576. And so, 17573, our mystery constant, is the smallest prime smaller than \(26^3\).

Therefore, given a single whole number smaller than 17572, we can exponentiate 57 to that power mod 17573, and get a number back. If we then reinterpret that number in base-26, and denote digits as follows:

- 0 -> Z

- 1 -> Y

- …24 -> B

- 25 -> A

we have successfully generated a three-letter capital-ASCII sequence from our number. And, moreover, we can generate all such three-letter sequences except three.

Now, in truth, in this particular instance there are several shortcomings that generally degrade the quality of the secret code construction.

First of all, the values of uVar3 and uVar2, which are the actual exponentiation factors that modulate the quality of generated secrets, generally do not allow for every possible three-letter sequence to be generated. Both of those values are generated by XORing two numbers smaller than 100. As numbers smaller than that always fit in the 7 rightmost bits, the result of the XOR can never be higher than \(2 ^ 7 - 1 = 127\). Which means that every single three-letter chunk generated ever can only be one of at most 127 possibilities.

Additionally, note that the code is generated by concatenating chunks of 3 letters, and each chunk is generated using either the first 2, or the last 2 digits of the secret code. Which means, that if you had 2 sets of codes, one of which was generated using a secret code with the same first 2 digits, and the other was generated using a secret code with the same last 2 digits, you could “splice” the sets together and get correct special codes for your secret code:

00 95 27 00 27 95

Baja Buggy XAR ZZY + YZZ IWQ = XAR IWQ

Jet OFY XZU + UZX FCS = OFY FCS

Hovercraft GOS FVA + AVF AVO = GOS AVO

Battle Tank NEJ AMA + AMA UQO = NEJ UQO

RC Cars CJR YHS + SHY IVZ = CJR IVZ

All Cars CXX BLD + DLB TBK = CXX TBK

All Tracks WQV KFB + BFK JRM = WQV JRM

All Parts YWE XUE + EUX YYI = YWE YYI

All Difficulties JGI UUR + RUU NDI = JGI NDI

Ford Super Focus OHW IPE + EPI SDO = OHW SDO

Observant readers will also notice that the parts of the secret codes generated from the 00 chunks above are the same, except with the character order reversed.

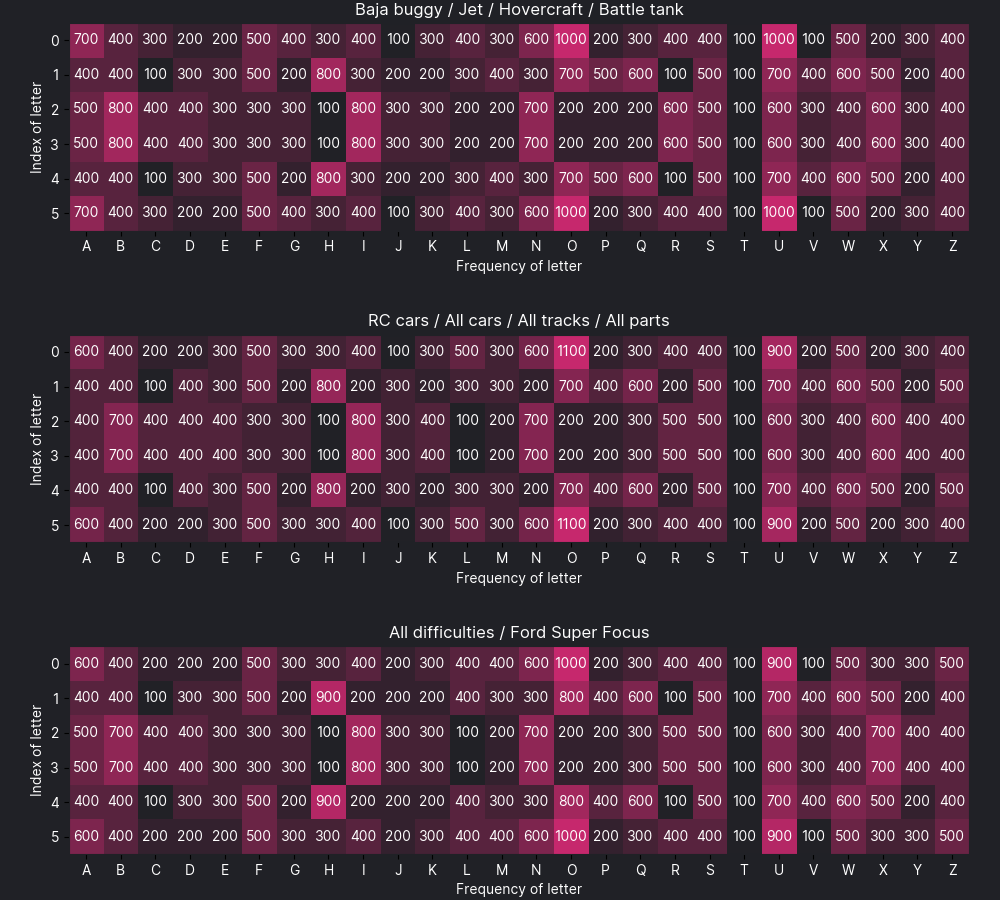

All of those caveats rear their head when empirical distributions of all possible special codes are plotted:

The plots above were constructed by taking all possible 10,000 “secret access codes”, and generating special codes for them. You will note: the symmetrical nature of the frequencies with respect to the index, and the fact that all frequencies are multiples of 100 (a corollary of the fact that each 3-letter chunk is decided by only 2 of 4 digits of the secret code).

As an aside, the distributions for codes with indices: 0 through 3, 4 through 7, and 8 through 9, are the exact same. I’m not exactly sure why this is the case. I don’t think that’s an error, though.

Of course, all of these “deficiencies” are obvious in hindsight. For a black-box thing, this was probably good enough. Those limitations may even have been intentional. For instance, I can imagine there being a “code book” for each of the 100 possible halves of the code, that an operator could read back from to assemble the final code? I guess we will never know.

The important thing is, that with the above deconstruction complete, I was finally satisfied. The secret codes were definitively at my will, and I could finally enable all of the secrets and rally race with an RC car. Or a hovercraft. Without having to get good at the game like a normal person.