Playing computer games has been one of my favourite pastimes for far too many years now. The idea of being able to make a game has been one of the forces that drove me to pick up programming. Unfortunately, with time I’ve learned that there’s a tremendous level of complexity involved in every non-trivial software project. As I’ve never actually completed a proper game with proper graphics before, I shall start small — with a clone of the classic game Sokoban.

Introductory notes

Sokoban is a puzzle game played on a two-dimensional grid. Each Sokoban level comprises of walls, crates and slots. The player controls a warehouse keeper, whose goal is to push the crates onto the designated slots. The main difficulty of the game is to manipulate the crates correctly, so that they don’t get stuck by the walls or get pushed into each other — one bad move could prevent further progress.

The choice of Sokoban for a first game is not accidental. It so happens that both the logic and display aspects of the game are relatively uncomplicated. Since the game takes place on a discrete two-dimensional grid, player movement around the levels should be easy to implement correctly. Actually displaying the game field is also quite easy — we’ll have a working display by the end of this post!

I will be using C# and the MonoGame engine to implement my version, which I called CratePusher. The choice is mainly caused by the fact that C# is the programming language I’m the most comfortable in — while I could use C++ and SDL like the real game developers do, CratePusher is not going to be a resource-intensive application by any means, so I’d rather take the performance hit (which I probably won’t notice anyway) and work in a reasonably familiar environment.

As for the graphics part of the equation, I’d like the game to look as polished as I can. Unfortunately, I do not have the skills to produce good game art — while I can design reasonably decently looking user interfaces, trying to draw anything anthropomorphic pretty much always ends in a disastrous failure for me. For this reason I will use the game assets gracefully provided by Kenney. Not only are those assets well-made and adhere to a recognizable and consistent art style, they are also licensed under the CC0 1.0 Universal license, effectively making them public-domain. At this point I’d like to thank Kenney for his providing those assets to aspiring game programmers, such as myself, so that they can use them in their first projects.

I would also like to say that this series is not intended as a game development tutorial. While I will be describing some techniques I find interesting or key during my progress, this is not a start-from-scratch tutorial to game development or programming altogether. I neither have the time or feel qualified enough to undertake the task of producing a real tutorial.

Now that the opening notes are done, let’s get into the meat of the problem!

Displaying a level

The aim of the first part of this series is to get the engine to render a single game level for us on the screen. In this way we will have a reasonable jumping-off point to start going into input handling and actual game logic implementation.

Working with tilesheets

As I’ve mentioned in the introduction, the two-dimensional grid nature of CratePusher allows for making significant simplifications. One particular simplification, often utilised in games of similar nature, is the use of tilesheets to render sprites (objects) on the screen.

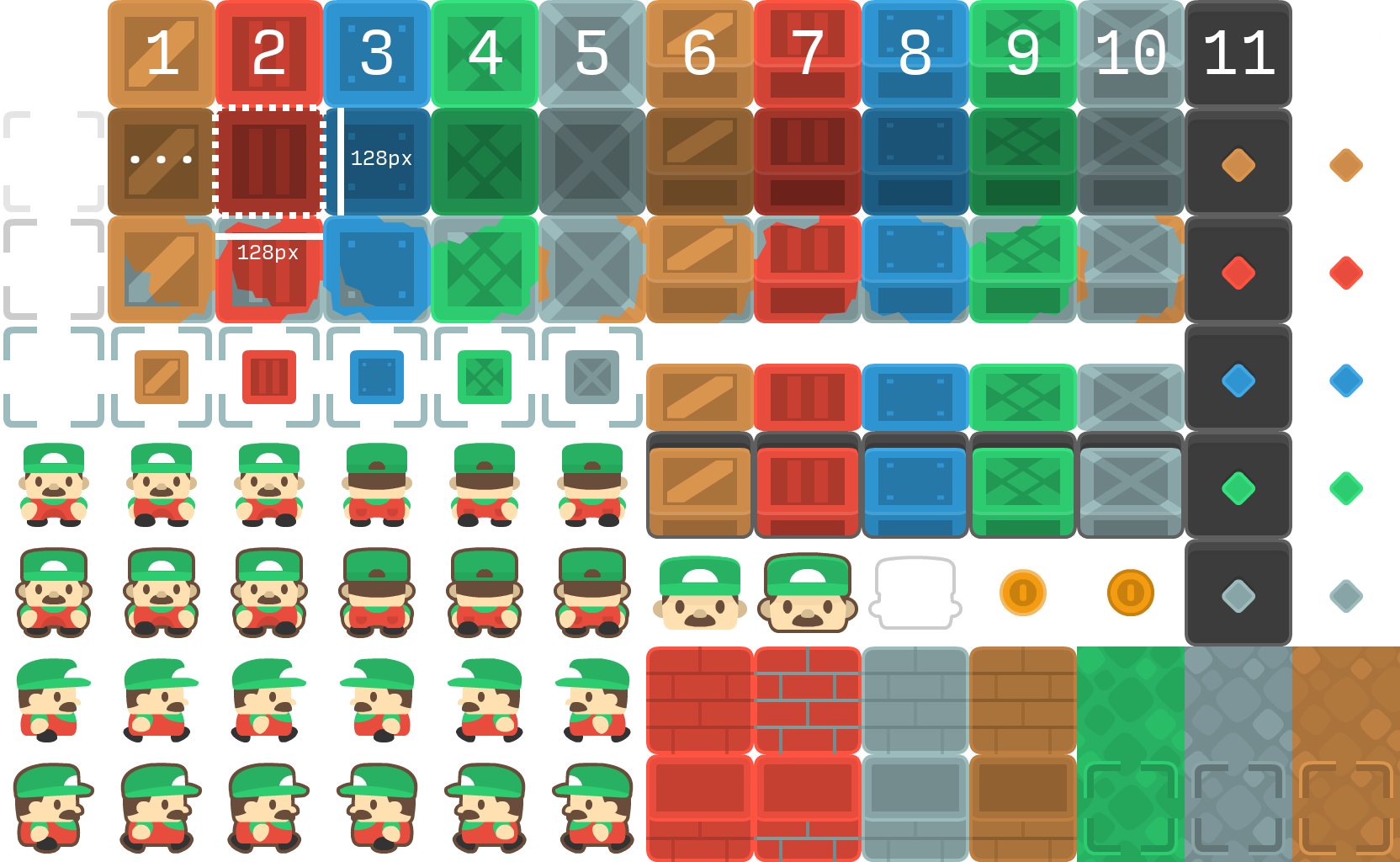

The tilesheet used in CratePusher. The numbers on the tiles represent the numbering scheme I used for rendering. In this particular case, each tile has the size of 128 by 128 pixels.

The tilesheet used in CratePusher. The numbers on the tiles represent the numbering scheme I used for rendering. In this particular case, each tile has the size of 128 by 128 pixels.

Tilesheets are single images, containing multiple sprites, aligned in a grid. For our use, the tilesheet is especially convenient, for multiple reasons:

- The use of a tilesheet means that we will effectively need to load only one texture image into the game.

- The MonoGame framework offers the

SpriteBatchclass for drawing two-dimensional images on the screen. As it happens, drawing a tile on the screen from a tilesheet is not that much complicated than drawing one from a single texture — so long as we do a little bit of math beforehand.

To draw a sprite off of the tilesheet, I need to compute the bounding box of the sprite first, represented by the position of the upper left corner of the sprite and its width and height. The width and height of the sprite is fixed, and is equal to 128 pixels. Computing the upper left corner coordinates is a little bit more tricky.

To be able to access the particular sprites I need, I introduced a numbering system depicted on the picture above, and added an enumeration type, mapping the tiles to their indices:

public enum TileType

{

YellowCrate = 6,

RedCrate = 7,

BlueCrate = 8,

GreenCrate = 9,

GrayCrate = 10,

TargetField = 11,

// ...

}

This way I will be able to draw any of my chosen tiles by referring to them by their name, instead of having to remember magic numbers. The numbering is actually all I need to uniquely compute the upper left corner coordinates of each tile, thanks to the wonders of modular arithmetic.

Notice that each row has exactly thirteen tiles in it.

This means that if I take the remainder of the tile index divided by 13 (\(i \mod 13\) in math speak), I will get the zero-based column number of the tile.

Analogously, dividing the tile index by 13 and rounding the result down (taking \(\left\lfloor \frac{i}{13} \right\rfloor\), to be more precise) gets me the zero-based row number of the tile.

Multiplying the resulting indices by the tile size yields the desired coordinates of the upper left corner of the tile!

At this point I let SpriteBatch do the rest of the drawing work, by telling it where to get the tile from and where to put it — and we’re ready to put some objects on the screen with our DrawTile function:

private const int Width = 13;

public const int TileSize = 128;

public void DrawTile(SpriteBatch spriteBatch, TileType type, Point point, int tileSize)

{

var idx = (int) type;

var x = idx % Width;

var y = idx / Width;

var sourceRectangle = new Rectangle(x * TileSize, y * TileSize, TileSize, TileSize);

spriteBatch.Draw(tileSheetTexture, new Rectangle(point, new Point(tileSize)), sourceRectangle, Color.White);

}

This function allows me to schedule drawing a tile of the supplied type in a SpriteBatch.

The tile will be drawn such that its top left corner will have the coordinates specified in the point parameter, and the tile width and height will be equal to tileSize.

This choice of parameters will become obvious at a later point.

Loading levels

After being able to draw, I set my sights on importing some levels into the game. Plain text files seem like an especially popular way of publishing Sokoban levels. In the files I’ve found, the following convention was assumed:

- Hash symbols (

#) indicated walls. - Dollar symbols (

$) indicated the stones to be moved around by the player. - Dots (

.) denoted the position of the target slots. - An at symbol (

@) denoted the initial placement of the player character. - Empty lines and lines starting with semicolons (

;) were level delimiters.

You could almost say that this format of storage resembles ASCII art. Thankfully, it is also not very hard to parse.

In my solution, there is a LevelImporter class responsible for importing the level collection.

It creates a single StreamReader instance and reads the whole file, and splits the levels apart.

public class LevelImporter : IDisposable

{

private readonly StreamReader streamReader;

public LevelImporter(string filePath)

{

streamReader = new StreamReader(filePath);

}

public LevelCollection LoadLevels()

{

var collection = new LevelCollection();;

var contents = streamReader.ReadToEnd();

var lines = contents.Split('\n');

var level = new List<string>();

foreach (var line in lines)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(line))

{

// Ignore empty lines

continue;

}

if (line.StartsWith(";"))

{

// New level starts; add the previous one to the collection

collection.Levels.Add(new Level(level));

level.Clear();

continue;

}

level.Add(line);

}

return collection;

}

public void Dispose()

{

streamReader?.Dispose();

}

}

The actual construction of the level is performed by the Level class constructor.

It performs the character-to-field-type mapping I mentioned at the beginning of this section:

public FieldType[,] Fields { get; }

public int Width => Fields.GetLength(1);

public int Height => Fields.GetLength(0);

public Level(IList<string> rows)

{

var height = rows.Count;

var width = rows.Select(r => r.Length).Max();

Fields = new FieldType[height, width];

PaintFloor = new bool[height, width];

Point? playerPosition = null;

for (int y = 0; y < height; ++y)

{

var line = rows[y];

for (int x = 0; x < line.Length; ++x)

{

switch (line[x])

{

case '#':

Fields[y, x] = FieldType.Wall;

break;

case '$':

Fields[y, x] = FieldType.Stone;

break;

case '.':

Fields[y, x] = FieldType.Slot;

break;

case '@':

Fields[y, x] = FieldType.Player;

playerPosition = new Point(x, y);

break;

}

}

}

if (!playerPosition.HasValue)

{

throw new ArgumentException("No player in level");

}

}

The exception at the end makes sure we have a player character in the level — this will come in handy at a later point.

Drawing, scaling & centering

Now I’ve got my drawing functions and data, I can move to displaying a single level on the screen. I could draw the level in the upper left corner of the screen without worrying about the resolution, but that is not a very usable solution. Therefore, I will attempt to center and scale the level, so that it always fits on the screen, but also maximizing the tile size at the same time to improve legibility.

Assume that we want the level to take up at most 90% of the screen’s width and height (so there’s a 5% margin on each side of the screen). This means that we have a cap on level dimensions, dependent on the screen dimensions. My level renderer computes this cap upon being constructed:

private const double MarginProportion = 0.9;

public LevelRenderer(GraphicsDeviceManager deviceManager, TileSheet tileSheet)

{

screenWidth = deviceManager.PreferredBackBufferWidth;

screenHeight = deviceManager.PreferredBackBufferHeight;

maxLevelWidth = (int) (screenWidth * MarginProportion);

maxLevelHeight = (int) (screenHeight * MarginProportion);

this.tileSheet = tileSheet; // We're also keeping a reference to the tilesheet, so we can draw whatever we need

}

A single level is a grid, of a given width and height in tiles. We can therefore calculate the maximum size the level can take up on the screen, assuming that we’re going to be drawing the tiles at their full size. If both the full width and height are less than the caps assumed, there’s nothing else for me to do than draw the level at 100% size. In the other case, I’m calculating the ratios of the full level dimensions to the maximum permissible dimensions and taking the minimum of them.

Example. Assume that a level takes up 800 by 800 pixels in full scale, while the permitted drawing area’s dimensions are 600 by 400 pixels.

- To make the level fit in width, I have to shrink it by \(\frac{600}{800} = \frac{3}{4}\)ths.

- To make the level fit in height, I have to shrink it to \(\frac{400}{800} = \frac{1}{2}\) of its original size.

I could of course scale both dimensions using different scales, but this will make the tiles seem stretched. Therefore I take the smaller ratio in both dimensions, to preserve the tile aspect ratio.

The resulting ratio multiplied by the full tile size gives me the size of tiles that I can afford to draw given the screen real estate allowed:

private int GetTileSize(int fullScaleWidth, int fullScaleHeight)

{

var desiredTileSize = TileSheet.TileSize;

// Make sure we actually can draw at full size

if (fullScaleHeight > maxLevelHeight || fullScaleWidth > maxLevelWidth)

{

// Calculate the scaling factor

var scalingFactor = Math.Min(

(double)maxLevelWidth / fullScaleWidth,

(double)maxLevelHeight / fullScaleHeight

);

desiredTileSize = (int)(scalingFactor * desiredTileSize);

}

return desiredTileSize;

}

Upon calculating the final tile size, I can move onto centering the level on the screen. This reduces to calculating the offset of the upper left corner of the level grid from the screen origin (the upper leftmost point on the screen, with assumed coordinates of (0, 0)). All tiles will be shifted by this offset. This is done by taking the difference between the screen size and level size on both dimensions and halving it.

public void Render(Level level, SpriteBatch spriteBatch)

{

var targetWidth = level.Width * TileSheet.TileSize;

var targetHeight = level.Height * TileSheet.TileSize;

var targetTileSize = GetTileSize(targetWidth, targetHeight);

if (targetTileSize != TileSheet.TileSize)

{

// Final level size

targetWidth = level.Width * targetTileSize;

targetHeight = level.Height * targetTileSize;

}

var offset = new Point((screenWidth - targetWidth) / 2, (screenHeight - targetHeight) / 2);

DrawLevelGrid(level, spriteBatch, offset, targetTileSize);

}

Notice that I am calculating the final level size purely off of the level grid dimensions and target tile size. I could have tried using the scaling ratio calculated earlier as follows:

targetWidth = fullScaleWidth * scalingFactor; targetHeight = fullScaleHeight * scalingFactor;However, there’s a pitfall in this solution. During these calculations, I would be rounding floating-point values to integers (I can’t really draw on non-integral coordinates). Therefore calculating the target level size individually could lead to me being a couple pixels off — the bigger the level size, the more likely an error is.

This pretty much concludes our calculations — now I’ll just put the TileSheet class to some real work:

private void DrawLevelGrid(Level level, SpriteBatch spriteBatch, Point offset, int targetTileSize)

{

for (int y = 0; y < level.Height; ++y)

{

for (int x = 0; x < level.Width; ++x)

{

var location = new Point(x * targetTileSize, y * targetTileSize) + offset;

switch (level.Fields[y, x])

{

case FieldType.Player:

tileSheet.DrawTile(spriteBatch, TileType.PlayerFacingDown, location, targetTileSize);

break;

case FieldType.Slot:

tileSheet.DrawTile(spriteBatch, TileType.TargetField, location, targetTileSize);

break;

case FieldType.Stone:

tileSheet.DrawTile(spriteBatch, TileType.YellowCrate, location, targetTileSize);

break;

case FieldType.Wall:

tileSheet.DrawTile(spriteBatch, TileType.RedWall, location, targetTileSize);

break;

}

}

}

}

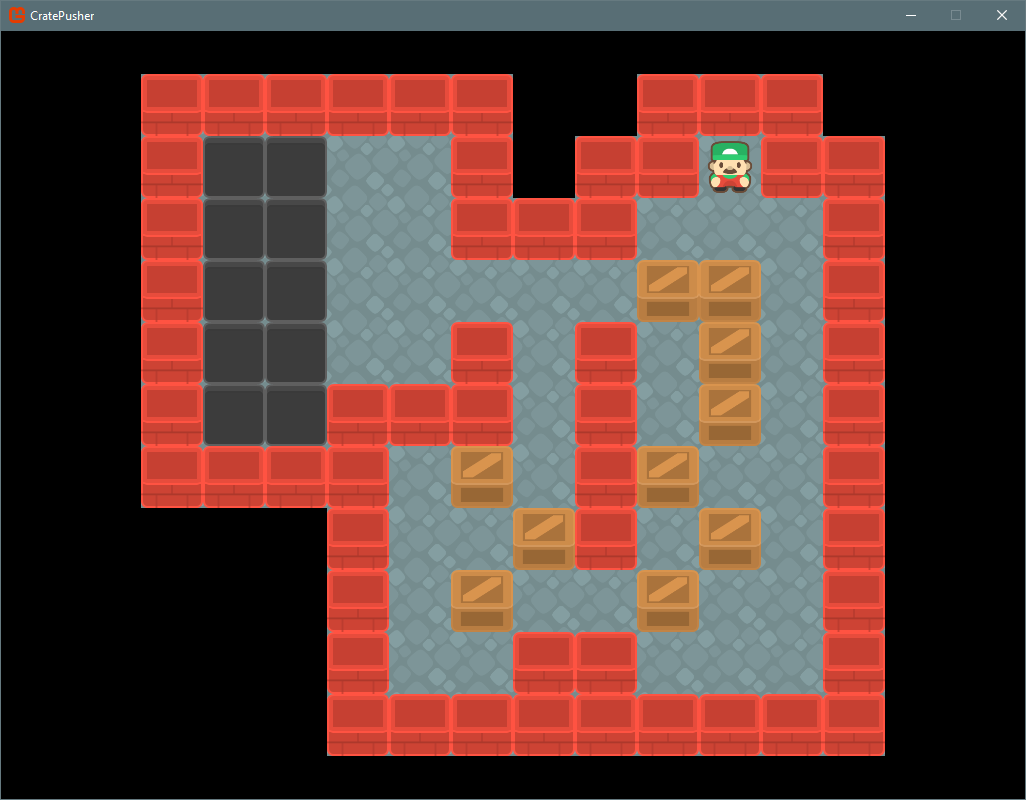

Running our program after supplying an example level results in this picture:

This looks pretty good — the level is centered, and the tiles scale well — but the empty tiles in the middle are not really to my liking. I have floor tiles ready in the tilesheet, so let’s find out a way to use them.

Flood filling the level interior

To fill the interior, I will need to expand our level importer logic a little bit. A technique called flood filling will come especially handy here.

Flood filling is commonly used in processing raster images (images made up of pixels). It’s a conceptually simple algorithm, that uses a collection data structure - either a stack or a queue.

The queue is similar to a real life queue. The items are added to the end of the queue, and taken out from the beginning of the queue.

On the other side, the stack resembles one of the rods used in the famous Tower of Hanoi puzzle; you can only take the topmost item off the rod (

popit off the stack), and you can only put an item over the top of the previous topmost item (pushit onto the stack).

Let’s move onto the description of the method. Before I start painting the interior tiles, I will change the level importer so that it draws the background behind every wall tile:

public bool[,] PaintFloor { get; }

public Level(IList<string> rows)

{

// ...

PaintFloor = new bool[height, width];

Point? playerPosition = null;

for (int y = 0; y < height; ++y)

{

var line = rows[y];

for (int x = 0; x < line.Length; ++x)

{

switch (line[x])

{

case '#':

Fields[y, x] = FieldType.Wall;

PaintFloor[y, x] = true; // here's where the tiles get marked

break;

After this initialization step, we can move onto the painting routine. It requires a single parameter — a tile to start from. This is not a problem, since the player’s initial position is an ideal choice of a starting point; it should by definition be within the maze. Here’s the annotated content of the flood-filling routine.

private void FloodFillFloor(Point playerPosition)

{

var positionStack = new Stack<Point>();

// List of neighbor tiles to be considered in each iteration

// The element tuples indicate offsets from the current point

// For example, the tuple (-1, 0) indicates a tile above the current one

// (the tile with the current y index minus one)

var neighbors = new List<(int, int)>

{

(-1, 0), (1, 0), (0, -1), (0, 1)

};

// Start from the player's initial position

positionStack.Push(playerPosition);

while (positionStack.Count > 0)

{

var nextPoint = positionStack.Pop();

var x = nextPoint.X;

var y = nextPoint.Y;

if (PaintFloor[y, x])

{

// If we've already painted this tile, skip it

continue;

}

PaintFloor[y, x] = true;

// Check every neighboring point

foreach ((var dx, var dy) in neighbors)

{

var newX = x + dx;

var newY = y + dy;

var point = new Point(newX, newY);

// Only push the new point to the stack, if it is within level bounds

// and has not been painted yet

if (newX >= 0 && newX < Width && newY >= 0 && newY < Height && !PaintFloor[newY, newX])

{

positionStack.Push(point);

}

}

}

}

To illustrate the algorithm, here’s a quick demonstration video. I have reduced the opacity of the player and crate sprites for clarity.

As you can see, the method exhaustively paints the entire floor of the level. Conceptually, you could equate this method to trying to walk in all directions from all tiles and seeing whether or not you’ve hit a painted tile.

Notice the little pause around 0:13; this is caused by the algorithm skipping over tiles it has already painted. The way the walk is performed may cause some tiles to be added to the stack multiple times, but notice that no tile will ever be added to the stack more than four times (since it has to be added from a neighboring tile). This, along with the fact, that our grid is finite, ensures that the algorithm will always terminate.

To round this off, here are two screenshots of levels, showcasing the background painting and scaling!

An easier level…

…and a harder one. Notice the tiles getting smaller.

What’s next?

This first post has turned out to be a lot longer than I had expected, so it’s probably best for me to finish this up for the time being. Now there’s a working display, I can move onto handling user input and implementing the actual gameplay of Sokoban, first using simple transitions. After that I will attempt to animate the sprites a little bit to get that extra bit of flashiness, and finish off the whole thing with some menus.

If you have gotten this far, thank you for reading this post and I hope you enjoyed it! The source code for this project is publically available at the CratePusher repository.

Until next time!