Most of the time debugging isn’t really much to write about, especially in C# land. In a language executing on a VM, with a managed memory model, most bugs are relatively shallow and easy to fix, except for the occasional race if you’re doing multi-threading - so when suddenly it appears that comparison of doubles has stopped working correctly, all bets are off.

About the only options available at that point that don’t result in loss of sanity are:

- give up investigating and accept that computers are fickle, unknowable machines, uncontrollable by your puny meat-based mind,

- spend a week of evenings looking at why the program you’re looking at apparently entirely fails at arithmetic.

From the fact that this post exists, you’ve probably guessed that I went for #2.

Math seemingly stops working

It all started with yet another GitHub issue, in which a user reported a crash after clicking around in the osu!lazer beatmap editor. (I won’t go into the particular details of what a beatmap editor is, as it’s mostly unimportant to the larger topic of this post.)

As is usual operating procedure, I, along with others, went to try to reproduce the problem on my Ubuntu install, and failed; it looked like it was going to be yet another irreproducible, and therefore inactionable, crash report.

The first “hail mary” came from the reporter themselves - they managed to ascertain that the crash only happened when the game was ran in single-threaded mode, and in a joint effort we’ve also managed to ascertain that it was also Windows-specific. This already bore the signs that it was going to be an interesting one to deal with - especially given where the crash was located at…

Without going through too much unnecessary detail, the bespoke framework that osu!lazer uses has the concept of bindables. A bindable is a wrapper around a value; a bindable can be, as the name suggests, bound to another bindable, and therefore bidirectionally receive and send value updates to and from the other bindable. This allows showing one particular value in multiple places on the UI, and ensuring that if one instance changes, the others will follow suit.

For numerical bindables, backed by floating-point values, the bindables have a built-in notion of precision, to prevent changes on the order of 1e-10 firing all sorts of callbacks when they don’t really matter.

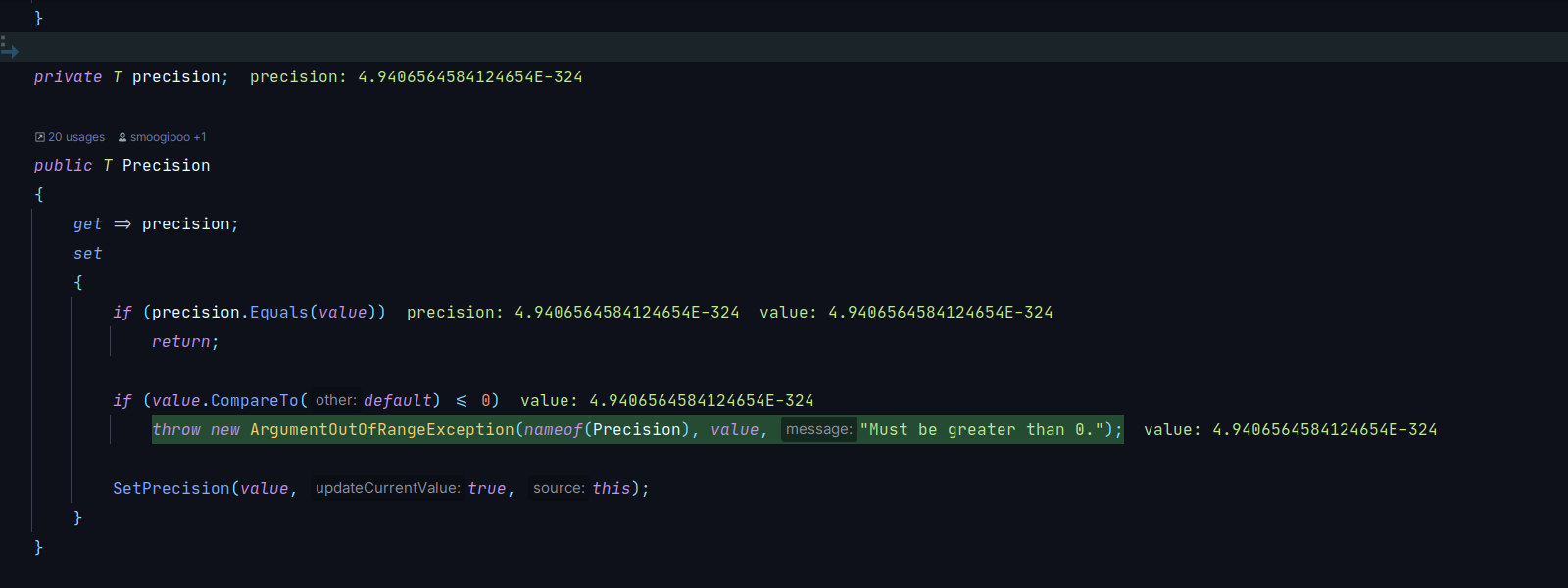

Here’s the implementation of the Precision property:

public T Precision

{

get => precision;

set

{

if (precision.Equals(value))

return;

if (value.CompareTo(default) <= 0)

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException(nameof(Precision), value, "Must be greater than 0.");

SetPrecision(value, true, this);

}

}

For some reason, on Windows, in single-threaded mode, setting Precision to double.Epsilon caused the ArgumentOutOfRangeException to be thrown, even though double.Epsilon is definitively larger than zero.

Debugger or no debugger, you could see value having 5e-324 in a watch and default being 0, and then the branch with the throw would be taken anyway, almost as if the fabric of reality was slipping from right under your feet.

It was clearly time to leave my beloved Rider, open up the rusty (but trusty) Visual Studio and get out the disassembly window.

After having enabled native debugging in the project settings and stepping into double.CompareTo(), I saw the following assembly code:

--- /_/src/System.Private.CoreLib/shared/System/Double.cs ----------------------

if (m_value < value) return -1;

00007FFA1F5307E0 sub rsp,18h

00007FFA1F5307E4 vzeroupper

00007FFA1F5307E7 vmovsd xmm0,qword ptr [rcx]

00007FFA1F5307EB vucomisd xmm1,xmm0 ; compare xmm1 to xmm0

00007FFA1F5307EF ja 00007FFA1F53084D ; jump if above (CF = 0, ZF = 0)

if (m_value > value) return 1;

00007FFA1F5307F1 vucomisd xmm0,xmm1

00007FFA1F5307F5 ja 00007FFA1F53085E

if (m_value == value) return 0;

00007FFA1F5307F7 vucomisd xmm0,xmm1

00007FFA1F5307FB jp 00007FFA1F5307FF ; jump if parity (PF = 0)

00007FFA1F5307FD je 00007FFA1F530857 ; jump if equal (ZF = 0)

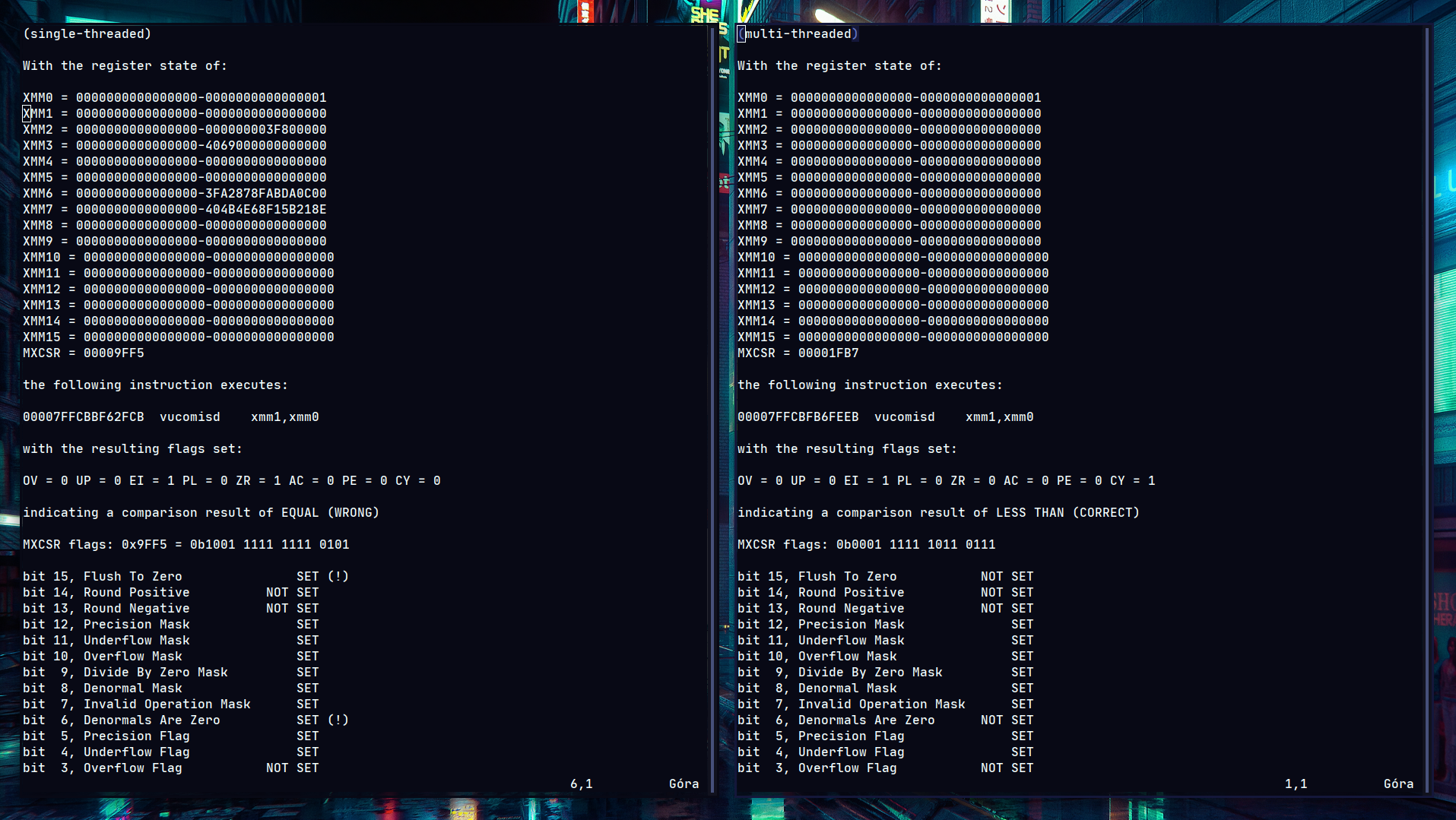

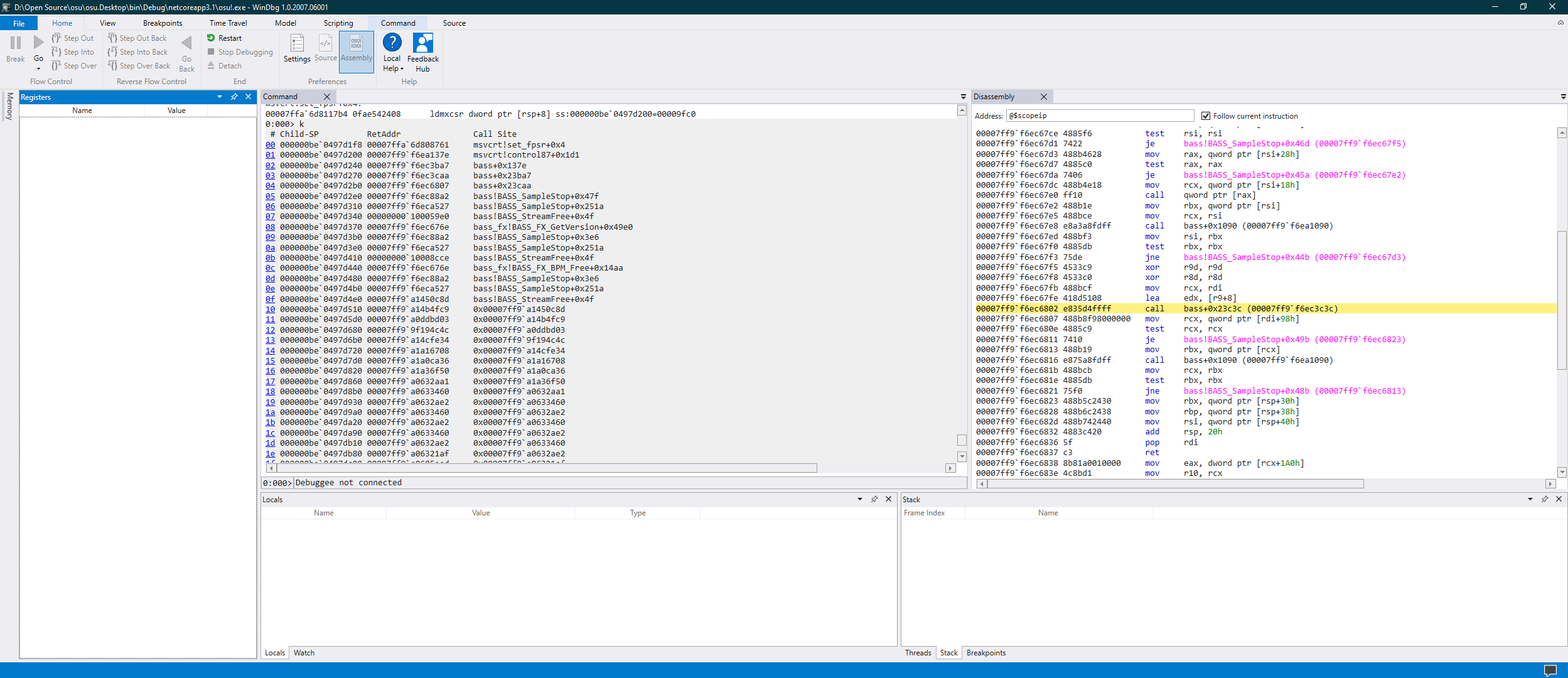

And, sure enough, I could definitely see that the execution of these instructions differed beteween multi-threaded and single-threaded mode. Using the “Registers” window I dumped the register state in both cases and got the following result (click screenshot below to enlarge):

xmm0 and xmm1 clearly have sane and expected values in both cases, so it definitely wasn’t a mis-store.

It was the comparison itself that was somehow wrong - but why?

I quickly (and, in retrospect, stupidly) went to confirm that the issue was CPU vendor-agnostic, and got the confirmation that it happens on both Intel and AMD CPUs.

About the only meaningful discrepancy seemed to be the mystery MXCSR value, so it was time to investigate.

A brief detour into SSE/AVX instructions

Before having departed on this journey, I have never really cared to look up anything about SSE/AVX registers. Any readers that possess such knowledge have already spotted the problem in the screenshot above, but for those that presumably have never looked into anything of the sort, this section aims to be a brief recap.

The vucomisd instruction is a - watch out - vectorised unordered compare of scalar double-precision floating point values that happens to return its result in EFLAGS.

Let’s break this down further into constituent parts:

- The vectorised part means SIMD (single instruction, multiple data).

SIMD instructions allow data parallelisation - on a concrete example, you can execute one common instruction simultaneously on

Ndifferent values at a time. Thankfully in this case that part isn’t really all that relevant. - The unordered part relates to

NaNs. In IEEE 754 floating-point math,NaNs are special (and annoying) values that fail every comparison they’re part of (so aNaNis neither less, greater than or equal to any other number, including anotherNaN). - Compare of scalar double-precision floating point values sounds about right for what we wanted in the C# code to begin with.

The result is returned in EFLAGS, which is a special quasi-register that is better viewed as a set of flags.

Here is the table describing the possible results of a vucomisd instruction:

| result | zero flag (ZF) | parity flag (PF) | carry flag (CF) |

|---|---|---|---|

unordered (one of operands is a NaN) |

1 | 1 | 1 |

| greater than | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| less than | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| equal | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Now, the MXCSR register is a special control register, in that it controls how the other SSE/AVX instructions execute.

In this particular case we’re interested in two related flags, one of which will turn out to be causing the madness.

- Bit 15 of the register is Flush To Zero (FTZ). Setting that bit will cause writes of denormal floating-point values to be coerced to zero.

- Bit 6 of the register is Denormals Are Zero (DAZ). Setting that bit will cause reads of denormal floating-point values to be coerced to zero.

This is immediately eye-catching in this particular scenario, as coercion to zero would definitively explain the differing equality result. However, to confirm, let’s define what a denormal value is (because I didn’t know either).

A denormal value is a floating-point value that has leading zeroes in the significand (so it’s of the form 0.00…1…). This can only happen if the exponent of the value is all zeroes - in that case, the implicit leading 1, normally assumed for any other exponent, is swapped for a zero. Therefore, the largest denormal double-precision value is

0b0 0000000000 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 = 2.225073858507201e-308

± |exponent| |--------------mantissa/significand----------------|

Because double.Epsilon is essentially a (uint64_t)0x1, it definitely is a denormal number.

And, sure enough, as the screenshot above demonstrates, DAZ is set in the single-threaded case, in which the issue reproduces.

Incidentally, MXCSR (at least on Windows) is part of the thread context, which explains why the multi-threaded mode worked fine - it’s incredibly likely that the change also occurs in multi-threaded mode, but doesn’t affect other threads, including the one that does the bogus comparison, therefore effectively “hiding” the issue.

That answers the immediate question of what’s going wrong, but now there’s a huge problem - anyone could be writing a value to a register at any time, so who is?

The floating point whodunit

This is about the point where I started freaking out.

The obvious first step for a programmer during a freak-out is to start frantically googling around for something that can be related, and so I made my way over to dotnet/runtime and started typing in vaguely related terms.

Surprise, it wasn’t an issue in the runtime itself, but I did find a few important clues:

-

First, I found calls to the

_mm_setcsr()x64 intrinsic, which set the value ofMXCSR:ResetProcessorStateHolder () { #if defined(TARGET_AMD64) m_mxcsr = _mm_getcsr(); _mm_setcsr(0x1f80); #endif // TARGET_AMD64 } ~ResetProcessorStateHolder () { #if defined(TARGET_AMD64) _mm_setcsr(m_mxcsr); #endif // TARGET_AMD64 }This clearly shows that the runtime is aware of what a

MXCSRis and it does try to restore the sane value of0x1F80, sometimes. I didn’t follow up on when, because I figured it was very unlikely Microsoft engineers would overlook something of this magnitude, and it was probably something that we were doing, directly or indirectly. -

Secondly, I spotted this comment:

// Return Value: // True if 'x' is a power of two value and is not denormal (denormals may not be well-defined // on some platforms such as if the user modified the floating-point environment via a P/Invoke)This rang several alarm bells immediately. As a cross-platform .NET Core game with a bespoke framework, lazer has to make a lot of P/Invokes and native calling to be a game. Combined with the fact that denormals/flush to zero are usually set by programs that need floating point performance (as processing denormals is slow), my list of immediate suspects included: BASS - an audio library (which we use ManagedBass as a wrapper for), and FFmpeg. BASS rose up in my personal ranking even further once I detected that in multi-threaded mode the thread dedicated entirely to audio playback also had a mangled

MXCSRvalue.

With that theory in hand, I did the most obvious thing that came to mind at first.

Because audio initialisation code is one of the earliest things lazer does when launching, I just figured I’ll start with stepping through the initial P/Invokes and keep an eye out for changes in MXCSR.

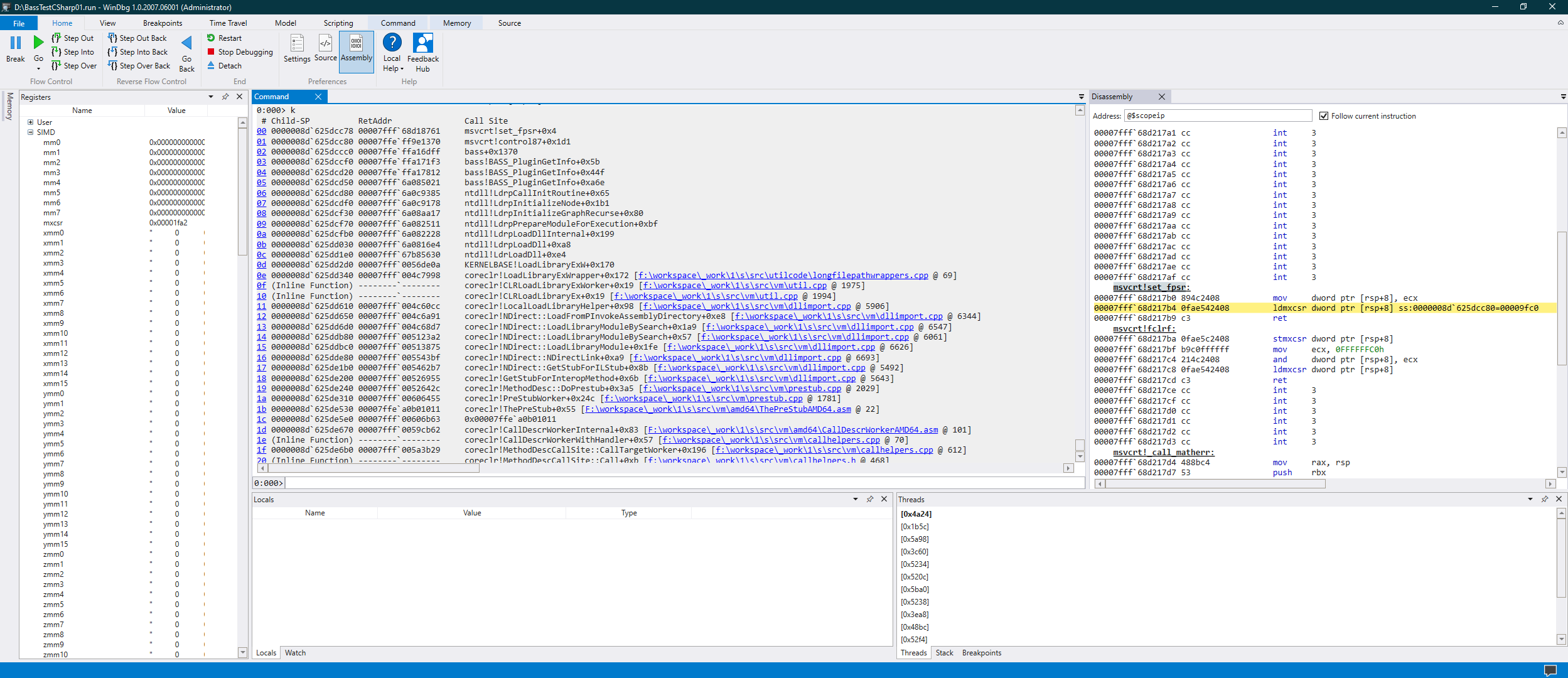

Sure enough, I did see a change after an audio sample-loading routine; this would have probably been enough to take it to the library maintainers, but I wanted to see the asm instruction that did it, and I was prepared to pull out the Tsar Bomba of Windows debugging, WinDbg.

(The link above leads to the Windows Store version of WinDbg. As much as I hate the Windows Store for existing, this particular version has two advantages over the classic crusty version, namely that the UI doesn’t look like it was pulled straight out of Windows 95, and that it has a new feature called Time Travel Debugging, which essentially records the whole program’s execution state, instruction after instruction, including the register values. This will come in very handy in just a minute.)

Making that happen in the game itself was pretty infeasible, all things considered.

With multiple threads, multiple libraries with debugging symbols, even attaching WinDbg took several minutes.

I also really wanted to use Time Travel Debugging with this, as you have to be very careful when stepping through code in WinDbg to not accidentally step over the call that changes the value (but which you don’t know if it does beforehand), therefore losing all your progress from the ongoing debugging session and having to start over and crawl your way through the call tree again.

To my chagrin, trying to use that feature with lazer resulted in sub-1-frame-per-second framerates and literal gigabytes per second in dump output.

Therefore, the obvious first thing to try was to write down the following equivalent of BASS “hello world” and cross my fingers that it would break the way I wanted it to:

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

namespace BassTestCSharp

{

public unsafe class Program

{

public static void Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine($"epsilon compared to 0 is: {double.Epsilon.CompareTo(0)}");

BASS_Init();

Console.WriteLine($"epsilon compared to 0 is: {double.Epsilon.CompareTo(0)}");

}

[DllImport("bass", EntryPoint = "BASS_Init")]

private static extern bool BASS_Init(int Device = -1, int Frequency = 44100, uint flags = 0x0, IntPtr win = default, IntPtr clsid = default);

}

}

And, yep, sure enough, I struck gold on the stupidest first try imaginable. The program would print:

epsilon compared to 0 is: 1

epsilon compared to 0 is: 0

Now, this program was small and simple enough for me to take a full snapshot of its execution with Time Travel Debugging. The only parts left to do to catch the bug red-handed was to slot into the proper part of the native BASS call and step over/into/back (stepping back was possible thanks to Time Travel) as long as it is needed to pinpoint the instruction.

Part 1 was easy enough, after I googled for and found the proper eldritch incantation of

sxe ld bass.dll

which in human language means roughly “raise me a first-chance exception (one that takes priority over all other exceptions) once bass.dll has started loading”.

Having arrived at the resulting breakpoint, somewhere near the entry point of BASS, the strategy was very simple:

- Step over the current instruction.

- If the instruction stepped over was a

callandMXCSRwas changed, step back and into thecall. - Repeat steps 1 and 2

ad nauseamuntil profit is achieved. - Profit:

There it is - a load of 0x9FC0 to MXCSR, as performed by the ldmxcsr instruction.

Curiously though, further down the stack, a call to LoadLibraryA can be seen, which indicated to me that all the C# stuff can be removed from the picture, and this should still reproduce.

Thusly, the following abomination of a C program was born:

#include "stdio.h"

#include "xmmintrin.h"

#include "windows.h"

void test_fp_state();

int main()

{

test_fp_state();

LoadLibrary("bass.dll");

test_fp_state();

return EXIT_SUCCESS;

}

void test_fp_state()

{

double a = 0;

int result;

long *a_ptr = &a;

*a_ptr = 0x1;

result = a > 0;

fprintf(stdout, "a > 0 is %d\n", result);

fprintf(stdout, "MXCSR is %x\n", _mm_getcsr());

}

Setting aside the unportability of the program (it assumes that a long and a double are both 8 bytes) and a flagrant violation of strict aliasing rules to simulate double.Epsilon in C (I didn’t want to bother googling if there was a more proper way to do this), this program prints the following:

a > 0 is 1

MXCSR is 1f82

a > 0 is 0

MXCSR is 9fe0

It’s almost beautiful how simple the resulting program was. Having gone through all that, I submitted the reproducer, the stack traces and all details I could think of that could be relevant to un4seen, and waited.

The very next day (huge, huge props on the turnaround time here), I received back another version to test with. Unfortunately, while both minimised reproducers were fixed, the game crash itself wasn’t. While I knew there was most likely some edge case missed, finding it was going to take a bit more effort.

Not out of the woods yet

The main problem with debugging this sort of thing in C# is that, well, CLR managed infinite-stack code is not native code, so I can’t just peek and poke values like in BASIC times. If I decided to go forward with stepping through each native call, I would still probably be doing so right now. It was time to cheat a little bit.

Knowing that C has the power to directly read/write MXCSR thanks to xmmintrin.h, the following thin DLL wrapper was born:

#include "pch.h"

#include "xmmintrin.h"

BOOL APIENTRY DllMain(

HMODULE hModule,

DWORD ul_reason_for_call,

LPVOID lpReserved)

{

switch (ul_reason_for_call)

{

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

__declspec(dllexport) unsigned ReadMXCSR()

{

return _mm_getcsr();

}

__declspec(dllexport) void SetMXCSR(unsigned value)

{

return _mm_setcsr(value);

}

(This is literally the first native DLL I’ve ever written in my life. Yes, I know the switch is pointless, it’s autogenerated by Visual Studio, and aims to show just how little of this stuff I’m aware of. Take it as inspiration - if I can stumble my way through this, then you probably can, too.)

Now that I had this DLL, I could P/Invoke it from C#, giving me all the power to read and mutate MXCSR whichever way I wanted to. That allowed me to make instrumenting BASS P/Invokes extremely easy, by writting the following utility class:

using System;

using System.Runtime.CompilerServices;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

using osu.Framework.Logging;

namespace osu.Framework.Utils

{

public sealed class IntrinsicDebugger : IDisposable

{

private readonly string caller;

private readonly uint initialValue;

private readonly uint bitMask = 0xFFFF_FFC0; // don't care about the flag bits (5-0)

public IntrinsicDebugger([CallerMemberName] string caller = null)

{

this.caller = caller;

initialValue = IntrinsicWrapper.ReadMXCSR() & bitMask;

}

public void Dispose()

{

uint currentValue = IntrinsicWrapper.ReadMXCSR() & bitMask;

if (currentValue != initialValue)

{

Logger.Log($"A native call inside of {caller} has modified MXCSR! (previous = {initialValue:X8}, current = {currentValue:X8}). Restoring previous.", level: LogLevel.Error);

IntrinsicWrapper.SetMXCSR(initialValue);

}

}

private static class IntrinsicWrapper

{

[DllImport("IntrinsicWrapper.dll")]

public static extern uint ReadMXCSR();

[DllImport("IntrinsicWrapper.dll")]

public static extern void SetMXCSR(uint value);

}

}

}

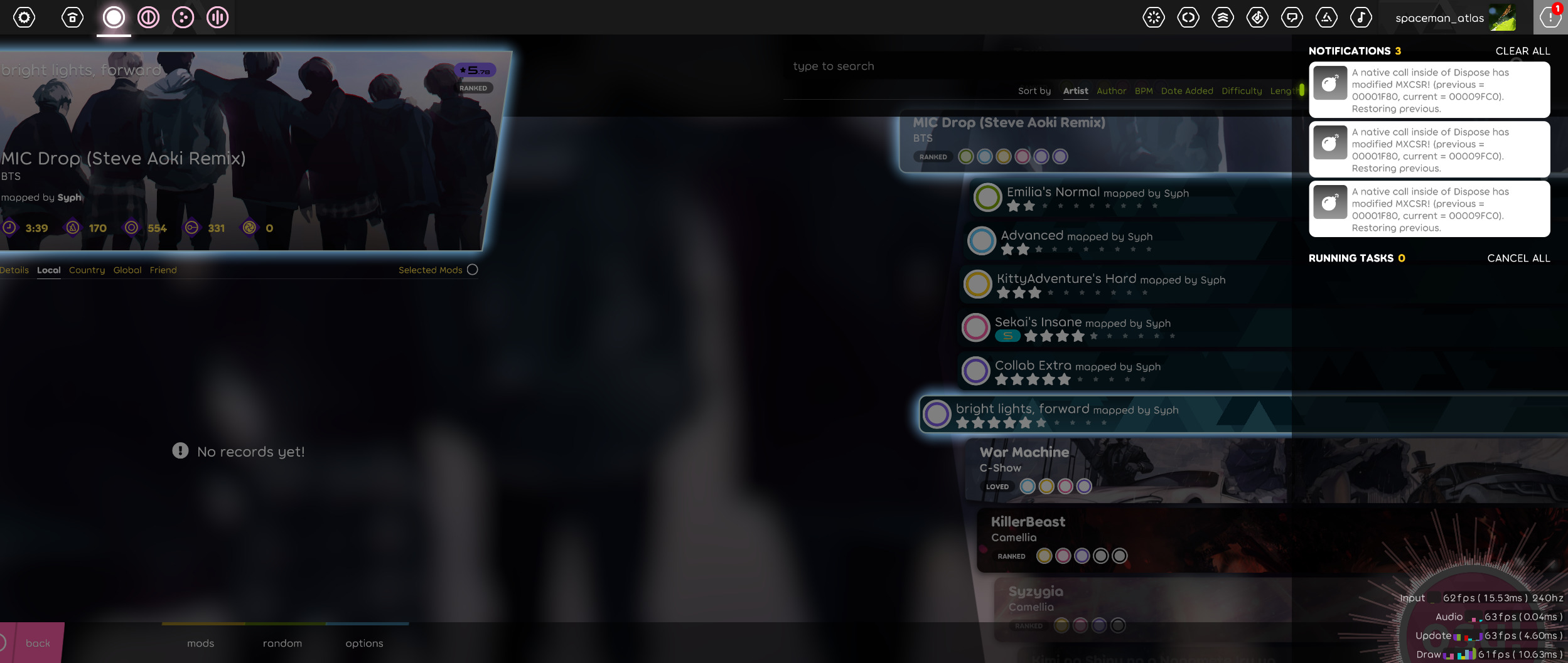

Now I had a whole slew of benefits:

-

Every change of

MXCSRwould get logged, which meant both an entry on disk and a nice notification (as shown on the screenshot below). CallerMemberName, or just breakpointing inside of thecurrentValue != initialValuebranch gave me the call site.- Because I could now restore

MXCSR, I could restore the game to a sane state, therefore making it possible to trigger the change multiple times in an execution without having to restart.

Equipped with the above, it became apparent incredibly quickly that the change was caused by switching songs in the game, and the underlying call that did the damage was a BASS_StreamFree.

It was time to summon the WinDbg Cthulhu again, and to enter the sacred scripture of

bp bass!BASS_StreamFree

which sets a breakpoint upon entry of the particular function affected, and is disappointingly a little less obtuse.

Unfortunately, due to the reasons mentioned once before in this post, as I was now debugging a live, multi-threaded game, I couldn’t rely on Time Travel Debugging, so the strategy changed a little, to:

- Step over instruction

- If the previous instruction modified

MXCSRand was acall, set a breakpoint there for the next re-run - Because

IntrinsicDebuggerrestored the old, sane value, now I only had to re-trigger the bug again, continue to the breakpoint set in point 2. and repeat the procedure iteratively until the call site was definitively located

This plan was foolproof enough to allow me to win again.

After delivering back the second stack trace, enjoying the weekend and getting back another tentatively fixed version the next week, it seemed that the error was definitively squashed. The bug-fix release of BASS with the version number of 2.4.15.25 seems to have definitely resolved the issue!

Conclusions

Before I go forward with any sweeping statements, I’ll fully acknowledge that the fact that I was able to track this down was a freak accident. I’m still not even sure how it happened; many a coincidence contributed on the way. That said I did still sink about a week and a half’s worth of evenings into it, so I did put in my fair share of time. In my estimates, tracking this down was about 10% luck, 20% skill, 15% concentrated power of will, 5% pleasure, 50% pain, and a 100% reason to get a decent blog post out of it in the end.

(Sorry. Now for the real conclusions.)

- Easily the most important thing is to isolate, isolate and once again isolate. Reducing the background noise in the debugging process is incredibly important to be able to analyse what’s going on, spot differences and scope down further. In some cases it is even necessary to remove all the unimportant stuff to be able to proceed using a tool that can help you (as was the case with WinDbg here).

- Instrumentation and tooling is absolutely key.

Without being able to inspect registers or step over assembly I would have either missed

MXCSRentirely, failed to spot how it was getting changed, or to pinpoint which code exact paths did it. - As long as you have a rough idea what is a good source and what isn’t, searching for resources online is tremendously important and let nobody ever tell you otherwise.

- Potentially “throwaway” comments like the ones over in the .NET Core runtime can actually help steer lost travelers away from madness. Jotting down non-obvious info like that comment mentioning denormals is insanely valuable and was easily the biggest individual leap in logic required to locate the source of all of this.

Finally, huge thanks again to Ian @ un4seen for responding very quickly to the reports and helping us out on very short notice. While it’s a closed-source library, it’s free for non-commercial use, and so it might be worth looking at even for open-source non-commercial, non-profit projects.

This blog might have peaked with this post, but hopefully there’ll be more debugging stories to come. I still have some untold ones I haven’t summarised yet, so I might get onto that if there’s interest.

Until next time!

Sep 18: This post was amended due to incorrectly stating that SIMD instructions work across multiple threads or cores. This is not the case, as they simply use larger, 256-bit registers, therefore allowing 4 double-precision values to be handled at a time. Thanks to /u/solraun from reddit for the correction!